The nurses are tired.

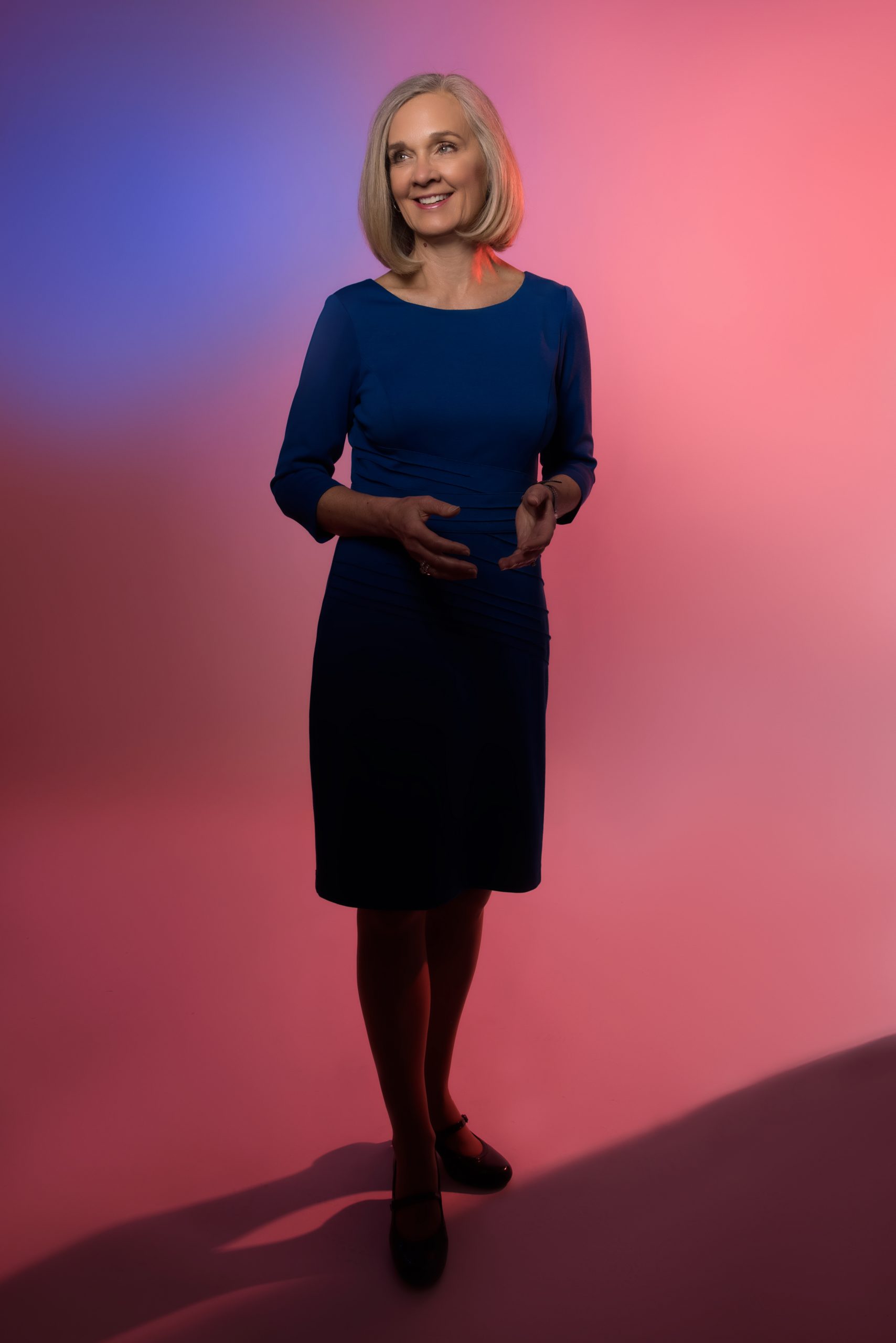

Audrey Wendt, who works at Spectrum Butterworth’s emergency room — right in the heart of Grand Rapids — is just one of them.

The job has been hard for a while. There was the earliest phase of the virus’ spread, when COVID-19 was new and strange, and the world raced to discover the best treatments. There was an almost forgotten phase when everyone thought the vaccine promised a quick exit from the pandemic.

Recently, Wendt recalled the virus at its worst. Michigan’s latest COVID surge was a slow burn that started in midsummer and worsened through the end of 2021, with cases steadily climbing. Michigan nurses took that surge on the chin.

“I would walk into work, and I had to walk this tiny path through our waiting room. Because there were so many people there just in wheelchairs and sitting anywhere and everywhere, lining up in the hallway there,” she said. “And it was almost eerie, because they’re almost all there for the same thing.”

In those days, Wendt didn’t know if she’d get called to an intensive care unit or be put on triage duty. Staffing the ICU has by now become the ultimate symbol of front-line work, but Wendt described patient screening as almost equally stressful — a job where a simple mistake could leave someone dying in the waiting room.

But if the virus was a burden, so too was the politics that started arriving at the emergency room last year. The last 12 or so months divided the country like never before. There are the masked, and the anti-maskers; the vaxxed, and the anti-vaxxers. Guess which ones end up at the hospital more often?

“It was almost like there was a seed that was placed in people’s minds that, ‘Maybe they’re lying about how bad it is,’” Wendt said, or that nurses might be lying about their financial incentives. “And that has never happened before. The whole time, I’m the same person showing up for work. But I’m a different face (to patients) than I was a couple months ago.”

Wendt recalled a woman who brought two elderly, sick parents, demanding that they receive Vitamin C and D. Because Wendt is not a doctor, she declined to guarantee any specific treatment.

“She started screaming at everyone in the waiting room, saying ‘They are not taking care of you, they don’t have your best interests in mind,’” Wendt said. “All I could do was just stand there and cry. It was just so ludicrous. It didn’t make any sense. You know you’re trying your best, but then you’ve got people — they don’t believe in you.”

It’s not personal, though it can feel that way. Her husband’s uncle died during the pandemic, marking one of the most painful blows Wendt has suffered in the past two years. Wendt said she’s taking an antidepressant as she continues to grapple with the stresses of work.

“I think we can all say that there’s probably a higher suicide rate for medical workers right now,” she said. “And I think a lot of people that I work with, including myself, are on, like, either medications for depression or anxiety, or they’re in therapy. Spectrum provides some counseling services, and I know a lot of people are utilizing that right now.”

A study published by American Journal of Nursing in November 2021, derived from a survey from before the pandemic, found 5.5% of nurses experience suicidal thoughts, a full 1% higher than other professions.

If Wendt’s story does not exactly sound like an invitation to join the profession, then you’re not alone. Nursing is suffering its worst workforce shortage in generations — hampered by the pandemic and the “Great Resignation,” as it’s colloquially known, in which Americans seem to be disavowing work en masse.

Nursing and other health care professions are perhaps the trend’s most dramatic example, where the cumulative effect of two years of a pandemic is thinning the ranks of a vital profession and turning the labor market on its head. At Spectrum, the better part of a thousand nursing and nursing support jobs — both full- and part-time — were posted on the company’s hiring network in early March. Some of them offered a $10,000 sign-on bonus.

Spectrum is not alone in that regard.

“From a nursing perspective, our turnover rate doubled what our baseline typically is,” said Michelle Peña, the chief nursing officer at Mercy Health Saint Mary’s in Grand Rapids. “We ran, pre-pandemic, about 9% to 10%. That has doubled.”

Peña said that number has started to drift downward again since the beginning of 2022.

But part of the problem — at Saint Mary’s and beyond — is stories like Wendt’s. Nursing, though it’s always been a tough job, is especially hard right now. But hospital leaders often argue that part of the problem is travel nursing — a lucrative option for nurses who are willing to relocate on a moment’s notice, to almost any part of the country, to bolster a hospital’s ailing nursing staff. Think of it like nursing special forces.

The problem for hospitals is that the pay is extraordinary, not only bleeding the budgets of health systems that need the extra hands but luring potential hires out of an already pinched market. Why make the average staff nurse’s salary when some nurses doubled or tripled their hourly pay last year — just by joining a traveling corps?

“That’s a serious and significant issue for nursing and some other disciplines, but primarily we’re seeing it in nursing right now,” said Shawn Ulreich, Spectrum’s senior vice prescient of clinical operations. “We know — we hope — that that is a short-lived phenomenon. But it’s been persisting for the last two years. And I suspect some of it will continue to persist in the future.”

But whether travel nurses are the problem or a symptom of something deeper depends on who you’re talking to. There’s a push to legally cap travel nurse pay; there’s also a push in the opposite direction, summed up neatly by a recent headline in Becker’s Hospital Review: “Cap hospital CEO pay.”

Mike Jura is a nurse at Mercy Health Muskegon. He’s worked alongside travel nurses — and even describes resentment, knowing that the freshly arrived travel nurse he’s training to work on his floor might be making far, far more than him.

But Jura’s frustrations are a lot bigger — and a lot deeper — than just travel nurses. Jura is a member of SEIU, the union that represents workers like him at Mercy Health Muskegon in contract talks with hospital brass that are stretching on amid reported tensions over wages and staffing shortages. The union voted to authorize a picket in early February.

“Mercy is in the community and reaping the rewards of the finances of the community that come into the hospital. I feel like they need to reward that staff, or at least pay them what they’re worth,” Jura said. “Because they’re great. They’re good people, and they put themselves on the line every day. They deserve better. I would encourage some of the higher-ups anytime to come down and, if they think they could do a better job, to try nursing for a day.”

A spokesperson with Mercy Health Muskegon provided a statement on the talks, which expressed disappointment that the union had recently voted down proposals that included retention and sign-on bonuses.

“Mercy Health Muskegon values our colleagues represented by SEIU, and we are looking forward to coming to a mutual agreement as soon as possible,” the statement, issued in early March, reads. “We have been very encouraged by the fact that the negotiating teams have been increasing the pace of negotiations, holding multiple meetings over the last couple weeks.”

Emily Fredericksen, a registered nurse at a Kalamazoo hospital, is a board member with the Michigan Nurses Association, the statewide advocacy group for nurses. Her proposed solution is the political opposite of capping pay scales. One of the best things leaders could do for nurses, Fredericksen said, would be mandated nurse-to-patient ratios — without which nurses and their workloads are “at the hospitals’ mercy.”

“We are always doing more with less. As things have evolved — charting and patients coming to the hospital sicker, higher acuity, those kinds of things — the nurse-to-patient ratios haven’t evolved,” she said. “Everybody’s doing more with less, and people get burned out and they leave.”

The pace at which nurses are burning out and leaving raises tough questions about how many more are waiting to replace them. Lola Coke, the acting dean of Grand Valley State University’s nursing school, said that there are already discussions underway about how to boost the number of nurses it educates as well as how to “streamline” curriculum without sacrificing quality.

One of the challenges is to make sure that nurses are ready for the reality of COVID-19 — namely, simulating bigger caseloads for nurses so that they can be ready for the stresses of being in a mid-pandemic hospital.

“They graduate and they become hired and they’re looking at maybe eight patients on a night shift or five patients on a day shift,” Coke said.

In many places, the pandemic hasn’t scared off potential health care workers — far from it. Aron Sousa, the interim dean of Michigan State University’s medical school, said applications have ticked upward since the beginning of the pandemic — more than 40% above normal during the first year of the virus, then 20% more recently. The profession is alluring to people who want to make a difference.

But they feel the drag, too — especially the ones who are on the front lines of the fight against COVID.

“The students have been in clinics and they’ve been in the hospital pretty much through the whole pandemic. I think they’ve experienced working in institutions that are struggling at a level that I didn’t as a student or resident,” he said. “The resident physicians, many of them had just month after month after month of six-days-a-week duty, because the hospitals have needed them. That’s just exhausting.”

It’s something that Sousa said he’s seen in person.

“The last time I was working in the hospital, I was working with one of the palliative care physicians because the COVID patient that we shared wasn’t going to make it,” he said. “That palliative care physician, that was her eighth consult for the day in COVID patients. The burden of death and suffering just went up so much for people who are working in the hospital and responsible for patients. And doing that day in and day out, that’s just a huge emotional toll to take.”

It’s not clear where the pandemic leads the health care field next; if the virus has proven anything over the last two years, it’s that the predictions are nearly worthless. COVID could fade to a background hum over the coming summer, as the scales fall from doubters’ eyes and vaccination rates soar. Or another dangerous variant could emerge. Such speculation is a fool’s errand.

But many health care workers describe feelings of optimism about the future, despite the toll the pandemic is now taking. One nurse who spoke to GR Mag said she’s “choosing to be hopeful” — focusing on the dramatic drop in cases that’s sweeping Michigan at the time of this writing.

There is no clear timeline for the virus’ end, though. Even in the best-case scenario, the world is on a medium-term path toward “endemicity,” in which concentrations of the virus are limited to certain areas. That’s not the same as COVID zero — nowhere close.

“People are starting to breathe a sigh of relief a little bit. There’s some hope that, OK, maybe we got through the last big surge,” said Liam Sullivan, an infectious disease doctor with Spectrum. But as much as there’s hope, he said, there’s also a sense of “weariness,” and the knowledge that a lull in infections brings no guarantees of a pandemic’s end.

“I sort of compare this virus to the crafty pitcher in the major leagues …. the virus came in as a fastball pitcher, and then we threw vaccines at it. And now this virus had to learn to throw junk, whether it’s a curveball, a slider, a sinker, a split-fingered fastball, or whatever,” Sullivan said. “So, it’s become the crafty veteran that is learning how to throw different ways at us that evade our defenses.”

For Wendt, the nurse at Spectrum Butterworth, the pandemic’s been overwhelming. But it hasn’t burned out her enthusiasm for helping just yet — that core of the profession that’s drawn so many people to become a health care worker in the first place.

“I feel like a lot of us are just kind of lost. We’re not really sure exactly what just happened to us,” she said. “I don’t want to sound like a whiny medical worker, like ‘I deserve compassion too.’ … but I think just being seen as a real person who is just trying to do the best they can” would be helpful.

“That is what I would want the community to know, is that we appreciate the trust that they put in us, and we take that so seriously,” she added. “We don’t want to do anybody wrong.”

This story can be found in the May/June 2022 issue of Grand Rapids Magazine. To get more stories like this delivered to your mailbox, subscribe here.

Facebook Comments